Bernese space exploration: With the world’s elite since the first moon landing

When the second man, "Buzz" Aldrin, stepped out of the lunar module on July 21, 1969, the first task he did was to set up the Bernese Solar Wind Composition experiment (SWC) also known as the “solar wind sail” by planting it in the ground of the moon, even before the American flag. This experiment, which was planned and the results analysed by Prof. Dr. Johannes Geiss and his team from the Physics Institute of the University of Bern, was the first great highlight in the history of Bernese space exploration.

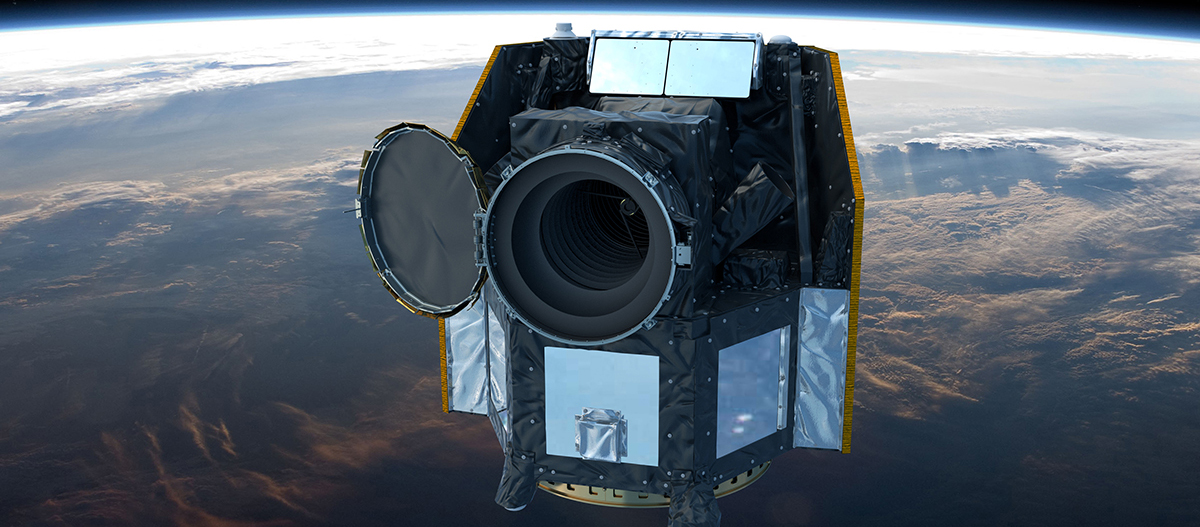

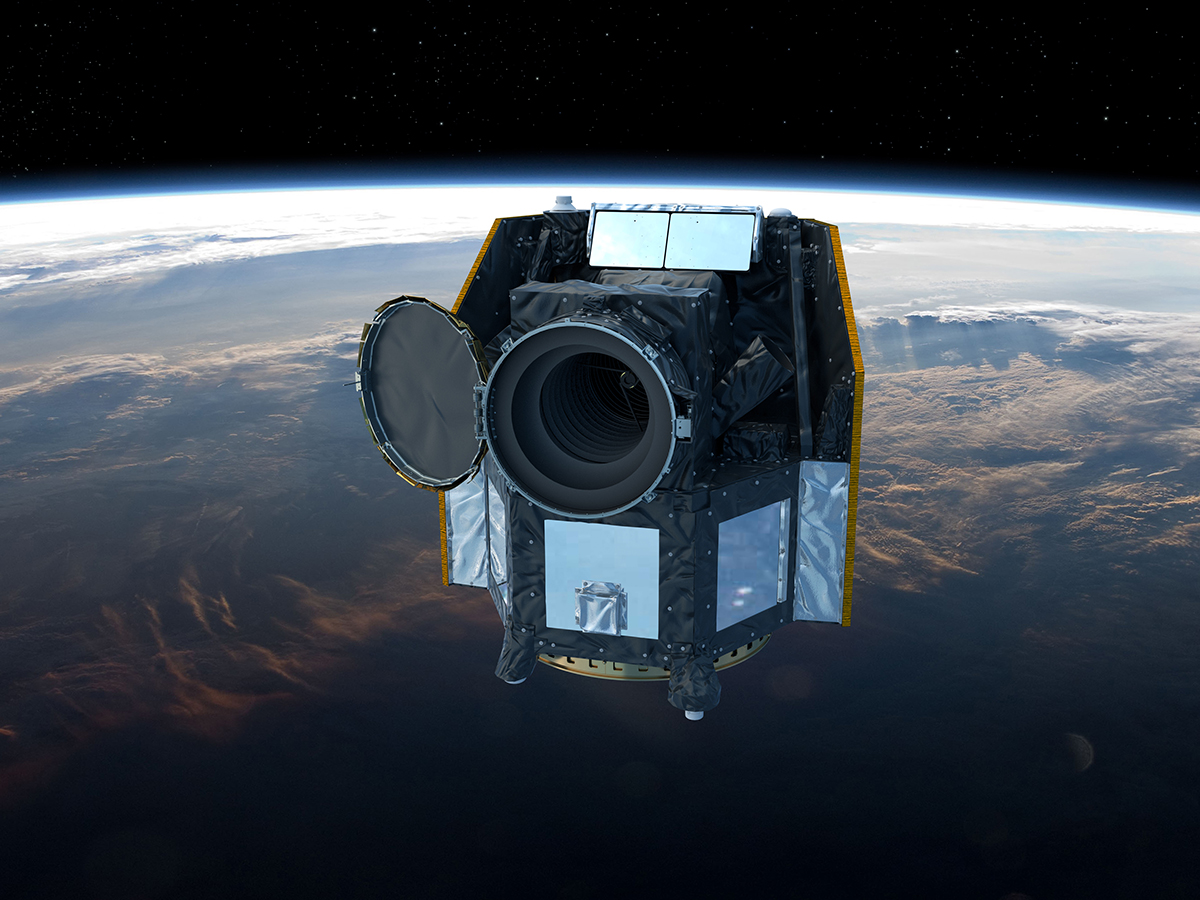

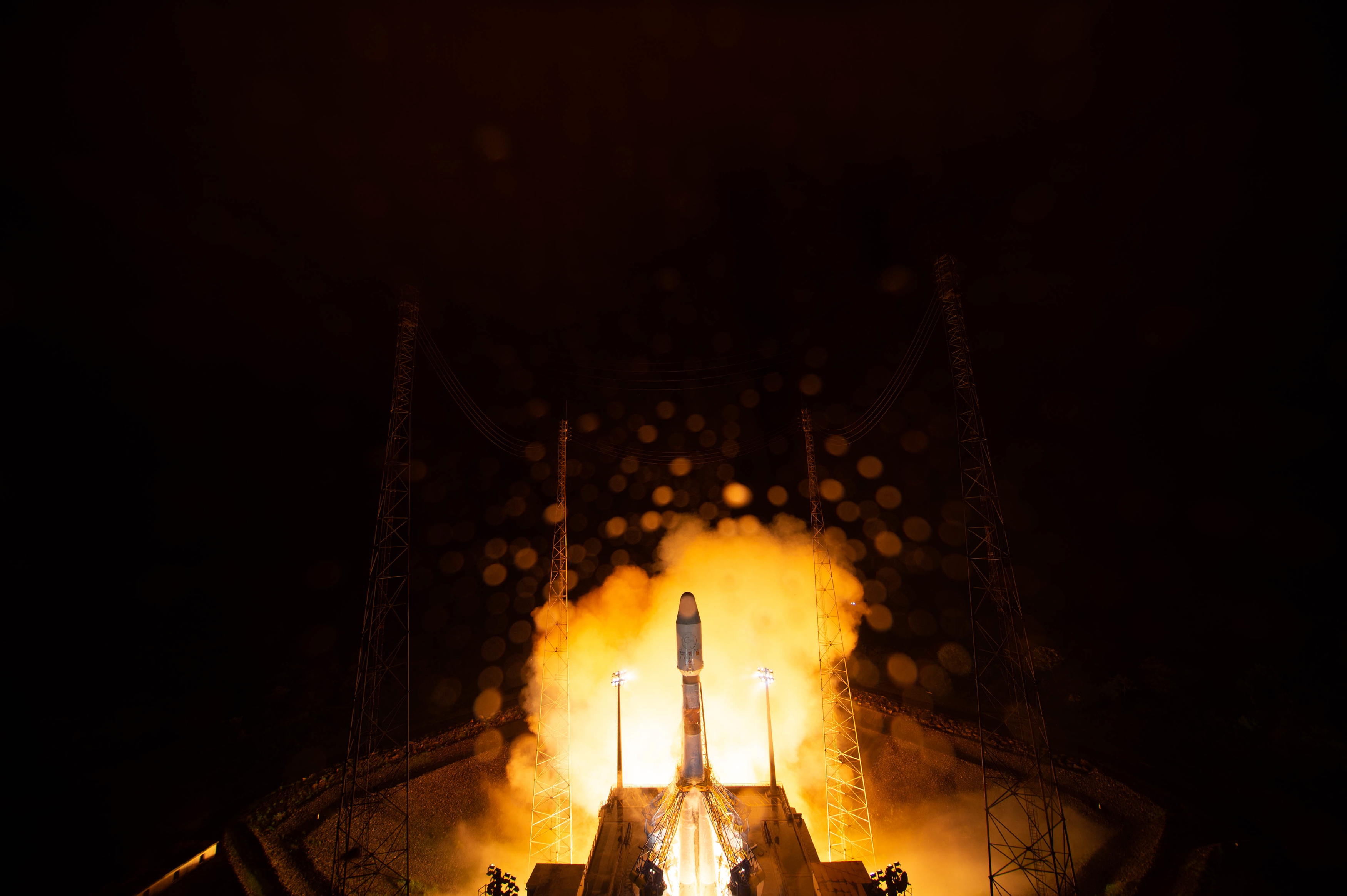

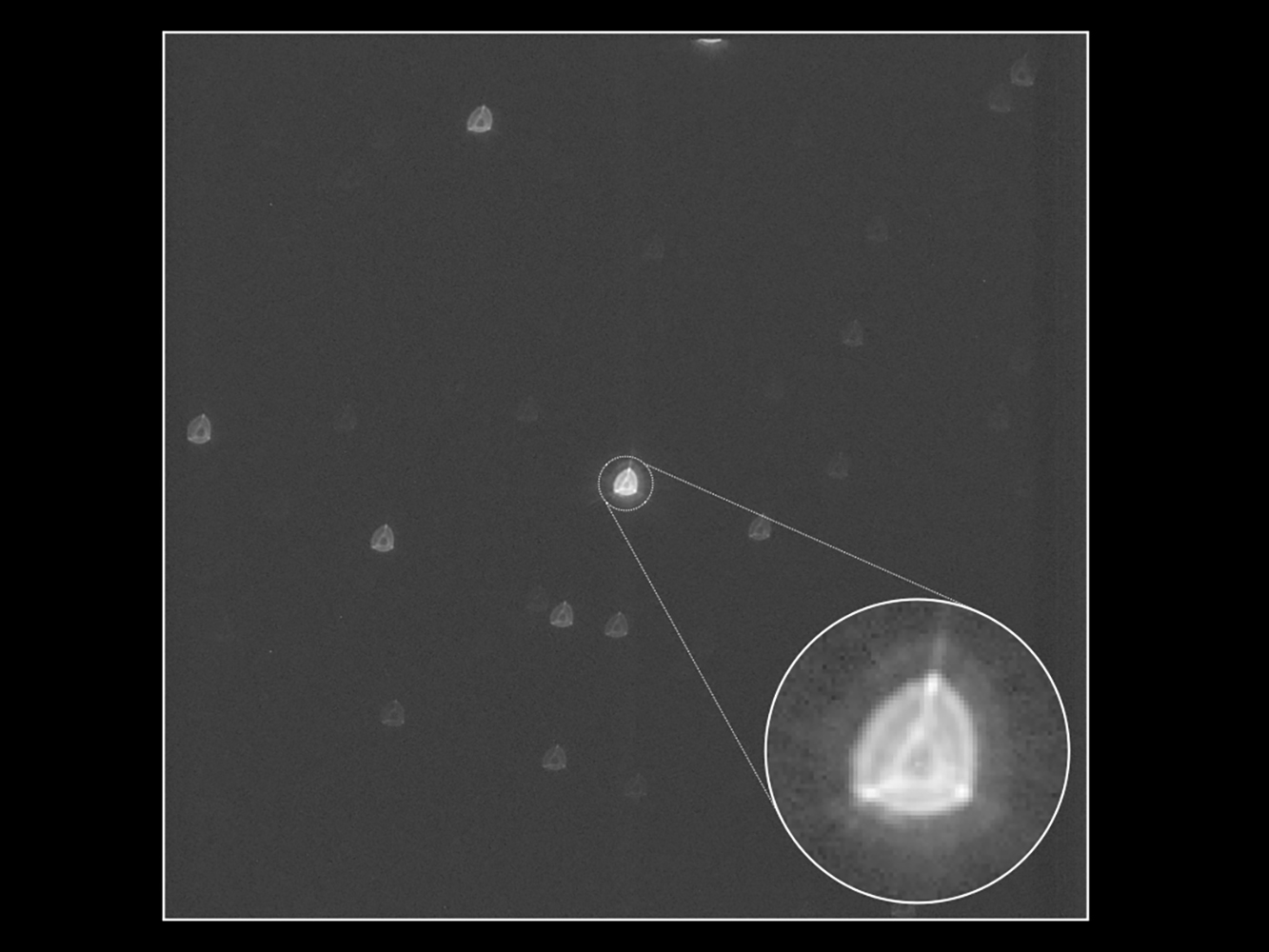

Ever since Bernese space exploration has been among the world’s elite, and the University of Bern has been participating in space missions of the major space organizations, such as ESA, NASA, ROSCOSMOS and JAXA. With CHEOPS the University of Bern shares responsibility with ESA for a whole mission. In addition, Bernese researchers are among the world leaders when it comes to models and simulations of the formation and development of planets.

The successful work of the Department of Space Research and Planetary Sciences (WP) from the Physics Institute of the University of Bern was consolidated by the foundation of a university competence center, the Center for Space and Habitability (CSH). The Swiss National Fund also awarded the University of Bern the National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR) PlanetS, which it manages together with the University of Geneva.